Monogamy evolved because of competition over inherited wealth, not to stabilize societies

The question of whether humans are “naturally” monogamous frequently appears in public debates and the media. Biology offers no simple answer. Humans share some traits with monogamous primates, where pair-bonding is often explained by the high demands of caring for slow-developing, highly dependent offspring. Anthropological evidence, however, complicates this picture. More than 80% of historically documented human societies have allowed polygyny, even though most people in these societies lived in monogamous unions.

Polygyny is more common in societies where men differ substantially in traits valued on marriage markets, such as health, wealth, and social status. Previous cross-cultural research shows that, at a global scale, such differences are strongly shaped by high pathogen prevalence and elevated levels of violence. Under these conditions, women may benefit from polygynous marriage—sharing a man who is healthy, wealthy, and capable of providing protection and material security for women and children.

This makes it all the more puzzling that a relatively small proportion of societies—often those that are wealthiest, most complex, and most socially unequal—have imposed monogamy as a legally enforced norm. Paradoxically, these are precisely the societies in which elites would seem to benefit most from polygyny, since they could afford multiple wives.

Two main theories have been proposed to explain this pattern. The first emphasizes competition between societies. According to this view, polygyny creates pools of unmarried men, increasing violence, crime, and social instability. By enforcing monogamy, societies are thought to reduce male–male competition, promote cooperation, and gain advantages in coordination, specialization, and military organization. In this account, monogamy functions as a form of social engineering designed to enhance long-term social stability and resilience.

The second theory approaches the problem from the perspective of families rather than societies. It links the emergence of normative monogamy to the growing importance of heritable wealth, especially agricultural land. As populations expanded and free land became scarce, land turned into a rival resource whose value declined when divided among many wives and heirs. Monogamy limits the number of legitimate heirs and helps keep property consolidated across generations. In this sense, it can be advantageous even for very wealthy men who have a strong interest in preserving family wealth over the long term.

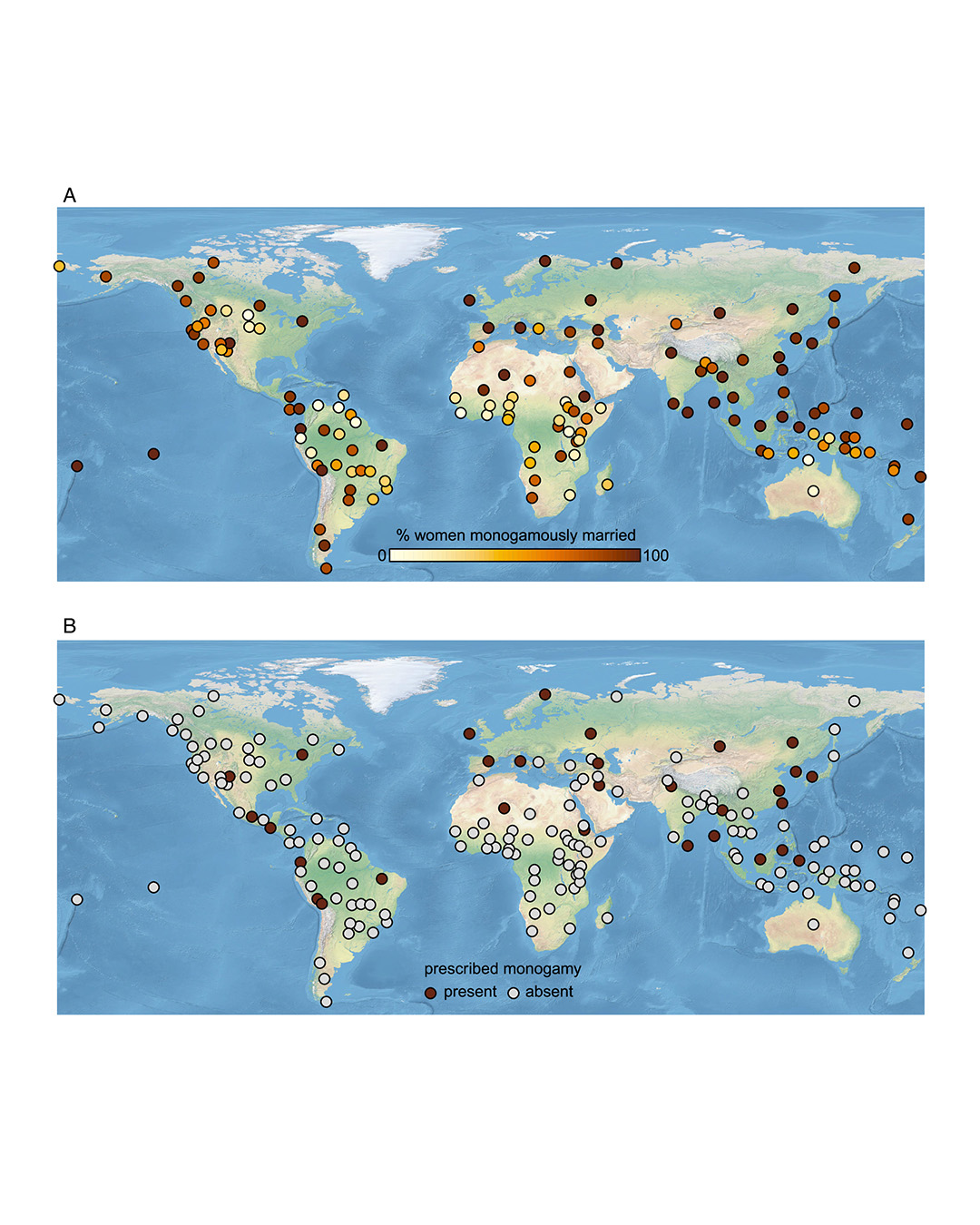

Researchers from the University of South Bohemia, together with colleagues from the United Kingdom and Switzerland, were the first to compare these two explanations systematically using global ethnographic data. They employed explicit causal models and Bayesian phylogenetic analyses on a sample of nearly 200 societies from different parts of the world, ranging from hunter-gatherer groups to ancient civilizations and historical states.

The results of the study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), provide strong support for the explanation based on inherited wealth. Across societies, monogamy is closely associated with the privatization of agricultural land and with ecological factors that make land scarce. By contrast, evidence for the social-stabilization hypothesis is weak and inconsistent: monogamy does not reliably reduce violence or increase cooperation in complex societies.

Normative monogamy thus appears to have evolved primarily as an adaptation to competition over property within families, rather than as a tool for reducing conflict between men at the level of whole societies. The study does not prescribe what marriage should look like today, nor does it assign moral value to monogamy. Instead, it offers a clearer understanding of why this particular form of marriage became so widespread over the course of human history.

Šaffa, G., Jaeggi, A. V., Zrzavý, J., & Duda, P. (2026). Competition for heritable wealth, not cultural group selection, drives the evolution of monogamy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 123(1), e2514328122.